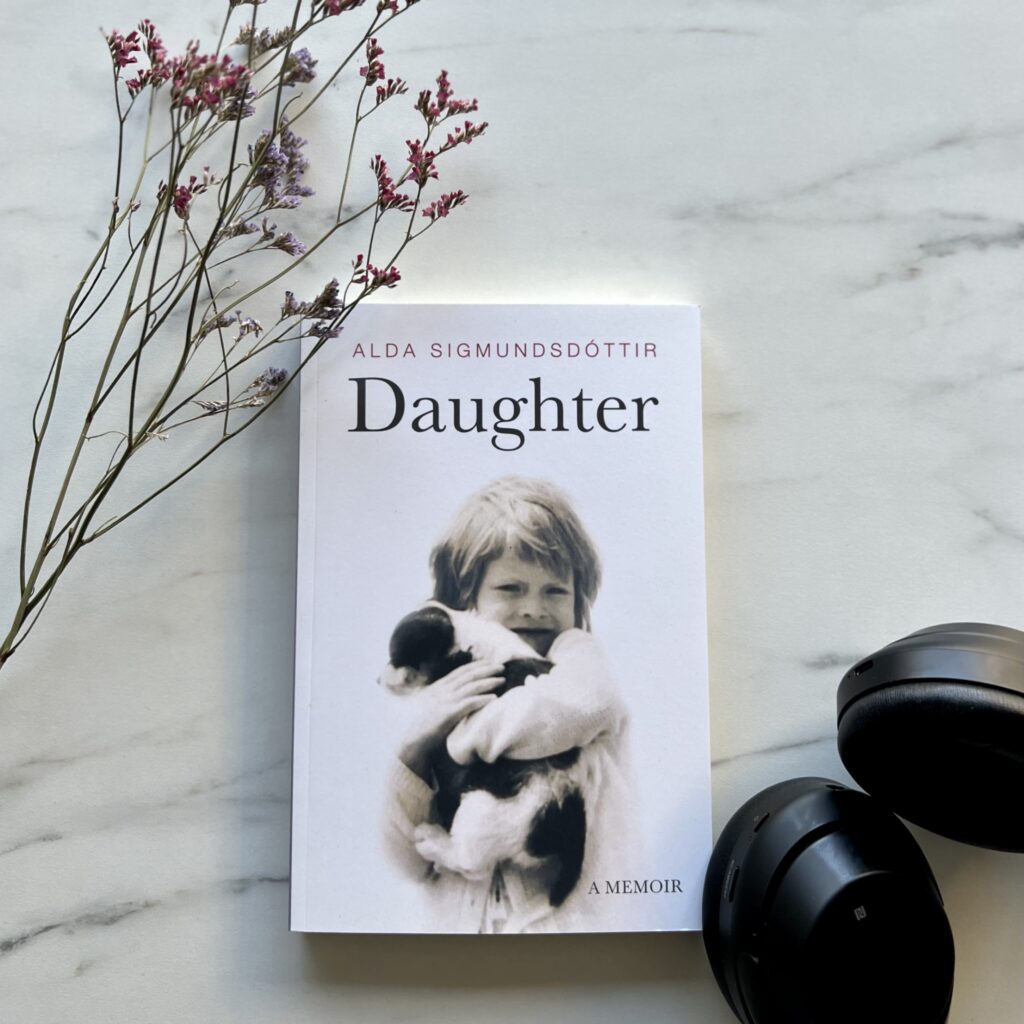

Daughter

a memoir

As a young girl, Alda Sigmundsdóttir yearns to be close to her beautiful, distant mother, yet is never able to win her affection. When her parents divorce, a dark symbiosis between mother and daughter is forged, with devastating consequences that threaten to derail everything—especially Alda’s chance at intimacy and love.

In this searingly honest memoir, the author of the beloved “Little Books” on Iceland tells the story of a childhood marred by trauma, the denial she employed to survive, and the struggle to regain her authentic self. In unpacking her personal history, Alda discovers the elusive nature of truth and its indispensable part in making us free. Inspiring, touching and brave, this book speaks to anyone who values emotional freedom and longs to break away from the destructive patterns of the past.

Á Íslandi fæst Daughter hjá Eymundsson og Bókabúð Forlagsins.

“Daughter is a work of bravery, an important and eloquent memoir about the fight to reclaim the self from those who seek to undermine and destroy our very existence. A must-read for anyone who has endured toxic familial relationships, and for those who seek to survive them.”

– Hannah Kent, author of Burial Rites

Daughter is now available as an audiobook!

read by the author. Listen to a sample below 👇

Sample chapter

When I was a little girl my mother and I fought all the time, so she decided that I should see a psychiatrist. I was eight years old.

On the day of the appointment, she picked me up from the daycare centre where I went after school and together we walked to the child psychiatric ward of the National Hospital. It took us around twenty minutes. It was springtime, and buds were just forming on the trees and bushes that we passed. The sun was out, but the air was still cool, and I shivered in my light winter jacket. My mother strode along purposefully and I strove to keep up with her, not sure what this meeting was for, or why I needed to go.

In the waiting area were a handful of chairs, and a low table designed for children, with crayons and paper. I did not sit at the children’s table but took a seat next to my mother, dangling my feet off the edge of the chair. A few minutes later a door opened and a tall man with a bulky physique and unruly hair stood in the doorway. He invited us into his office and introduced himself as Karl. He took a seat behind a big desk, my mother and I sat opposite, and after they had conversed for a bit he began asking me questions: What was my favourite subject in school; what did I like to do in my spare time; how did I get along with my mother; how did I feel about my father living apart from us? Eventually he pulled out a piece of cardboard that had been folded in two, and opened it. In the middle was a blob of something.

“Does this remind you of anything?” he asked, watching me closely.

I leaned closer to examine it, then looked at him, puzzled. I wanted to give him the right answer, but was confused. He gave a genial smile. “Just tell me if you think this looks like anything.”

It looked like a big blob of ink to me, but obediently I said: “It’s kind of like an elephant.”

He glanced at the blob and nodded thoughtfully.

“Very good,” he said. “I’m going to talk to your mother now and was wondering if you would mind going out into the hall and drawing me a picture?”

“Of what?”

“Anything you want.” He smiled benignly.

I went out and glanced back to see the door close behind me. I sat at the low kid’s table and got to work.

By the time the door opened again my masterpiece was ready. I had drawn a house with a chimney and a garden, a flag pole with the Icelandic flag at full mast, a tree, and a winding path leading to the door. I handed the picture to the doctor, sincerely hoping he would like it.

“That’s a good picture,” he said, taking his seat behind the desk again. “I notice there are no people in it.”

“I’m not good at drawing people,” I said.

More questions ensued, then I was sent out into the hallway again for a few minutes while the doctor and my mother wrapped things up.

Later that evening I overheard my mother on the phone, telling her eldest sister Alma about the session. The doctor’s verdict was that I was normal. Our fighting was also normal, and stemmed from the fact that we were too much alike, he said. If we ever stopped fighting, he told my mother, that was when she should bring me to see him.

There was a hint of triumph in her voice as she said it, as though this gave her some kind of one-upmanship. Which I would later learn was, indeed the case—my mother and Alma disagreed when it came to child-rearing methodology, and my mother was very keen to prove Alma wrong, and herself right.

I now know that Karl had no idea what he was looking at. None. Although how could he have been expected to see the threads that were woven in secret and kept resolutely hidden behind the façade of loving motherhood? Even I, who was the most immediate party to them, was unable to view the insidious tapestry they were weaving.

It was not until my half-sister Frances came to visit me, some four decades later, that I saw the evidence laid out before me, crystal-clear. Frances, who was nearly twenty years my junior, was sitting at my kitchen table wearing her Queen’s University varsity jacket, while I was at the sink rinsing some dishes. I do not recall the exact topic we were discussing, only that she suddenly said: “I know why you didn’t come to visit. I know it was because of my dad.”

I had been standing with my back to her, and now spun around. Before I had a chance to comment she raised her left hand, made a sharp movement across it with the index finger of her right hand, and said emphatically: “If I could rid myself of his DNA by cutting my own wrists, I would do it.”

Her dark, almond-shaped eyes—our mother’s eyes—burned with an acrimonious fire. I knew, right then, that I could not say what I was thinking: that her father was an easy man to hate, but that there was more—so much more. I could not say it because of her evident presumption that we were allies, that she and I were united with our mother against her father. That it was all about him, and in no way about her.

And then, with a creeping sense of dread, came the absolute inner knowing that where my mother had failed with me, she had succeeded with Frances.

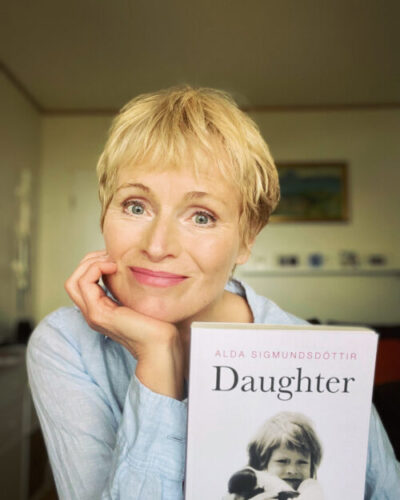

About the author

Alda Sigmundsdóttir is a writer, and occasional journalist. She runs her own independent press, Little Books Publishing, based in Reykjavík, Iceland.

Alda is the author of ten books, each of which explores an aspect of Icelandic culture or society. Her two latest books, The Little Book of the Icelanders at Christmas and The Little Book of Days in Iceland, are about the Icelanders’ enthusiasm for the Yuletide season, and Iceland’s special seasonal events and holidays, respectively. Alda is active on social media, and may be found on Facebook, Instagram and Substack.